Cain: A Rootless Cosmopolitan

Weekly Torah reflections from Matthew Schultz, a rabbinical student at Hebrew College.

Welcome to Torat Ha’Aretz. Weekly Torah reflections that read the text through the lens of the Jewish connection to the land of Israel and the idea of exile.

If you like these essays, please consider learning with me! I’ll be teaching a class called Judaism for the End of the World online starting in November. Click here for details!

Cain: A Rootless Cosmopolitan

East of Eden, Adam and Eve conceive and bear a son, Cain. They then have a second son, Abel. This will be the first of many pairs of rival brothers described in the book of Genesis.

Abel becomes a herder of sheep and Cain a tiller of the soil. In the fullness of time, Cain brings an offering to God from the fruit of the land. Abel also brings an offering, selecting the “choicest” firstlings of his flock.

But while God “turns to” Abel’s offering, He ignores Cain’s. No reason is given for this seeming injustice and Cain’s is greatly distressed—perhaps even enraged.

God asks him, “why are you distressed and why is your face fallen?”

We can only wonder what would have happened in the story if God had waited for an answer. Instead, He hurries to offer a solution:

“Surely, if you do right, there is uplift. But if you do not do right, sin crouches at the door; its urge is toward you, yet you can be its master.”

We might call this the first covenant that God makes with human beings. But as with all those that follow, the human quickly falls short of his commitments.

Cain comes upon his brother in a field. Words are spoken, but mysteriously, the text refrains from telling us what they are. “Cain said to his brother Abel,” but exactly what was said failed to echo through eternity.

The rest of the story is well known, but also widely misremembered. Cain strikes his brother dead. When asked by God as to Abel’s whereabouts, he retorts, “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

But God already knows the answer to His own question. “Your brother’s blood cries out to Me from the ground” (4:10, JPS 2006).

For his sin, Cain is condemned to a life of a restless wandering. He can fathom no greater punishment, and cries out that it is too much for him to bear. As Shakespeare wrote, “exile hath more terror in his look, much more than death.”

God then places a mark on Cain. This is the detail that gets misremembered. People recall the mark of Cain as a sort of scarlet letter designating him as an outcast. In truth, it is a mark of divine protection so that no one will harm Cain in his wanderings.

God may not have taken interest in Cain’s offering, but He does take interest in Cain’s sorrow, sin, and remorse. In this sense, Cain has indeed emerged victorious over his brother.

There is a flatness to Abel. Well behaved, he offers his choicest animals to God, but that’s the end of his agency in this story.

Cain, on the other hand, is interesting—both to God and to us. God loves him not because he does everything right, but because he is dynamic, vulnerable, and perplexing even to his own creator. He brings something new into the world. Murder, yes, but also repentance. Also intimacy. The relationship between Cain and God after their rupture is more intense than God’s relationship with Abel at its best.

As to what the mark of Cain looked like, it is suggested in Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer that the mark was a letter from God’s own name. It is a bit of Torah worn upon the skin—a kind of proto-tefillin.

Indeed, the same word used to refer to tefillin in the Torah, “ote” or sign, is used to describe Cain’s marking. The word is also used to describe circumcision. Cain, then, is a proto-Jew.

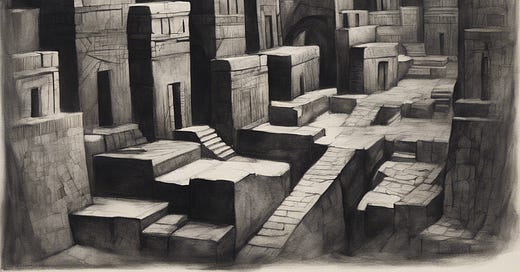

He goes on to marry and have a son called Enoch. The text tells us that he then founded a city and named it after his son.

Founded a city? Was he not cursed to be forever on the move? Eli Weisel suggests the following solution: “Does it mean that one can remain in one place and still be in exile? Probably. Exile is not necessarily linked to geography.”

Especially true when we’re discussing a city. It is in the urban environment specifically that one can remain a ceaseless wanderer while staying in the same place.

By the Middle Ages, Jews were already associated with cities, largely because of limitations on their legal right to own land. It was thus in the city that the more ancient antisemitic myth of the wandering Jew—the wretched Hebrew condemned to wearily tread the earth until Christ’s second coming—transformed into the modern antisemitic myth of the Jew as “rootless cosmopolitan.”

The rootless part is meant quite literally. Today, Jews often point out the irony that Israelis are told to “go back to Europe” when, less than a century ago, Jews in Europe were regularly told to “Go back to Palestine.” For the antisemite, however, there is no irony. Both statements are valid. The Jew belongs to no place, and that’s his own problem.

In Howard Jacobson’s 2010 novel “The Finkler Question,” the eponymous Finkler rebuffs an anti-Zionist saying, “'How dare you, a non Jew…how dare you even think you can tell Jews what sort of country they may live in, when it is you, a European Gentile, who made a separate country for Jews a necessity?”

For Zionists, there is indeed a plain hypocrisy when the same world that systematically expelled Jews from nearly every country on earth also condemns them for building their own country in historic Palestine.

But again, for the antisemite, there is no hypocrisy. For him, the long history of Jewish persecution is not a justification for the existence of a Jewish state. More often, they see it as proof positive that Jews are impossible to get along with.

As one individual asked me on Instagram, “109 countries kicked you out. If you got kicked out of 109 apartments, would you keep blaming the landlord?”

Cain’s exile is more wretched than that of his parents. They at least had a homeland to dream of, a memory of rootedness to keep them warm. Cain was exiled from exile, and condemned to be forever on the move.

As if this ignoble ancestry would be too much for humanity to bear, the Torah writes Cain’s lineage out of the story.

Adam and Eve have a third son, Seth, who will be the ancestor of Noah, who alone with his family will survive the great flood. Cain’s descendants will drown.

They will not, however, disappear. Their legacy, while not genetic, will endure.

The Torah records that Cain’s grandson Yaval is the “ancestor” of all those who dwell in tents and raise herds. This phrase directly evokes the Torah’s later description of Jacob, the father of the people of Israel: “Jacob was a mild man, a dweller of tents” (Genesis 25:27).

Cain’s other grandson Yuval is the ancestor of “all those who play the lyre and pipe.” We may be reminded of King David, who played a secret chord that resounded in the palaces of heaven.

So Cain, the first man to have God’s name become a sign upon his flesh, is the ancestor of Jacob, the archetypal Jewish sojourner, who learned that God is not bound up anywhere, and can be stumbled upon as one travels along the way.

But he is no less the ancestor of King David, who built God’s mighty house in the eternal city of Jerusalem.

Interesting. I never thought of Cain in the way you interpret him. Thanks.

Too long, dear Matt. Very interesting point of view and thought provoking as usual. ❤️⭐